Sitte ge, sīgewīf,

sīgað tō eorðan,

næfre ge wilde

tō wuda fleogan,

beō ge swā gemindige,

mīnes gōdes,

swā bið manna gehwilc,

metes and ēðeles.

Old English. Anglo Saxon metrical charm.

Sitte ge, sīgewīf,

sīgað tō eorðan,

næfre ge wilde

tō wuda fleogan,

beō ge swā gemindige,

mīnes gōdes,

swā bið manna gehwilc,

metes and ēðeles.

Old English. Anglo Saxon metrical charm.

~1874~

A rustic, preparing to devour an apple, was addressed by a brace of crafty and covetous birds:

“Nice apple that,” said one, critically examining it. “I don’t wish to disparage it — wouldn’t say a word against that vegetable for all the world. But I never can look upon an apple of that variety without thinking of my poisoned nestling! Ah! so plump, and rosy, and — rotten!”

“Just so,” said the other. “And you remember my good father, who perished in that orchard. Strange that so fair a skin should cover so vile a heart!”

Just then another fowl came flying up.

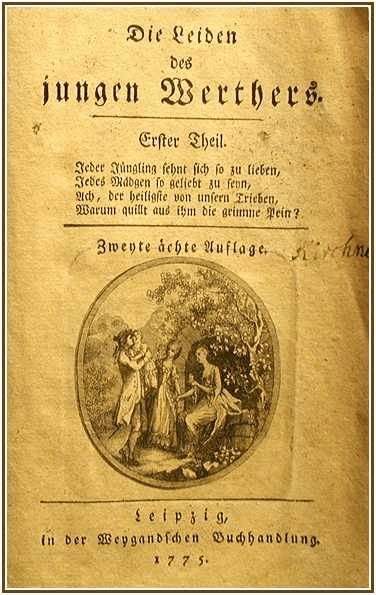

This inconspicuous looking text was the impetus behind a rash of suicides in the late 18th century. Written by Goethe, this epistolary novel followed the sorrows of a young man whose true love is betrothed to another. The book accounts the man’s decent into depression and ultimately suicide.

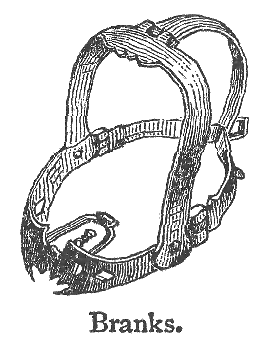

The Scold’s Bridle, also known as “branks,” was a piece of equipment used to punish and oppress women in the fifteen and sixteen hundreds. The bridle was made of an iron frame that encased the head of the victim. At the front of this contraption, a bridle “bit” piece extended into the mouth, holding down the tongue with a spiked plate, rendering the victim mute. In effect, a scold’s bridle was a muzzle used on human females.

What type of crimes deserved such a punishment? Women were bridled for being “gossips,” “scolds,” “riotous,” “troublesome,” and even on suspicion of witchcraft.

~Edward Lear, 1835~

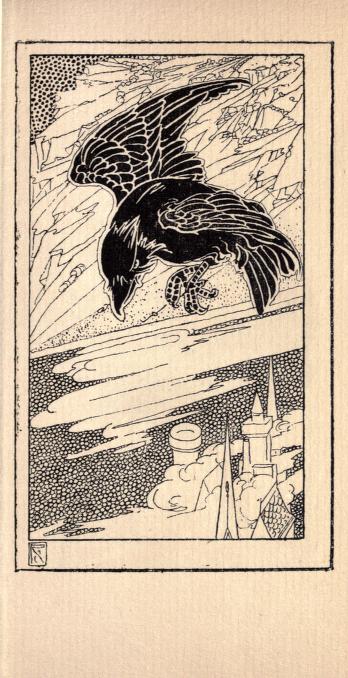

~ From Aesop’s Fables, Robinson edition, 1895~

A Crow, ready to die with thirst, flew with joy to a Pitcher, which he saw at a distance. But when he came up to it, he found the water so low that with all his stooping and straining he was unable to reach it. Thereupon he tried to break the Pitcher; then to overturn it; but his strength was not sufficient to do either. At last, seeing some small pebbles lie near the place, he cast them one by one into the Pitcher; and thus, by degrees, raised the water up to the very brim, and quenched his thirst.”

Santa Muerte de mi corazón,

Niña Blanca,

Ampárame bajo tu manto

Y otórgame tu bendición

Para que el amor y la dicha siempre lleguen

Señora Mía dame tu fuerza

Para que todo lo que me rodea se armonice.

Para que la fortuna y la suerte me sigan siempre.

Que todo lo malo se retire

Que todo lo bueno venga.

Te lo pido por tu poder y fuerza sobre todas las cosas vivas.

Amén.

Excerpts of H.P. Lovecraft’s The Rats in the Walls, 1924

~with~

visions of the legendary Rattenkönig, the Rat King, 1683

God! those carrion black pits of sawed, picked bones and opened skulls! Those nightmare chasms choked with the pithecanthropoid, Celtic, Roman, and English bones of countless unhallowed centuries! Some of them were full, and none can say how deep they had once been. Others were still bottomless to our searchlights, and peopled by unnameable fancies. What, I thought, of the hapless rats that stumbled into such traps amidst the blackness of their quests in this grisly Tartarus?

My searchlight expired, but still I ran. I heard voices, and yowls, and echoes, but above all there gently rose that impious, insidious scurrying; gently rising, rising, as a stiff bloated corpse gently rises above an oily river that flows under the endless onyx bridges to a black, putrid sea. Something bumped into me — something soft and plump. It must have been the rats; the viscous, gelatinous, ravenous army that feast on the dead and the living …